Service-linked roles (SLRs) are probably not something you should care about. And yet, they’re so peculiar that you are reading this professional blog post about them.

We’re coming in hawt peoples. And you know this ain’t AI slop because of the spelling mitsakes and grammar bad.

What makes service-linked roles special is that they:

- Are created by

aws iam create-service-linked-roleAPI - Cannot be created using

aws iam create-roleAPI - Are deleted by

aws iam delete-service-linked-roleAPI - Cannot be deleted unless certain conditions are met

- Cannot be deleted using

aws iam delete-role - Have the path

role/aws-service-role/ (notice it’s not “service-linked-role”) - Start with the prefix

AWSServiceRoleFor(notice it’s not “ServiceLinkedRole”) - Have a managed policy attached with the path

policy/aws-service-role/ - Are owned by AWS, not the customer

- Cannot be edited (except for description) by the customer

No vulnerabilities were discovered or disclosed during the creation of this blog post. All PR teams can stand down while us nerds discuss fascinating security implications and optimizations.

If you like this post, you might also like Things You Wish You Didn’t Need to Know About S3.

Background

Service-linked roles are NOT the same thing as service roles. No matter how many UI elements or documentation pages make them sound like they are. In fact, AWS uses the terms interchangeably whenever it feels good. However, they have important differences.

From my totally definitely exhaustive analysis, service-linked roles were created to bootstrap AWS services, or resources in services, that had dependencies on other services.

A service-linked role is a special type of service role that gives the service permission to access resources in other services on your behalf.

Each service can define a service-linked role for itself, including trust policy and managed resource policy. Some services apparently can have more than one service-linked role, although I haven’t observed this in the wild. Services are responsible creating, modifying, and deleting their service-linked roles. Here’s how it works for IAM Identity Center inside Organizations.

That’s a weird security model. Not all the way weird, but weird. Ultimately AWS owns and has access to all the things, in the physical sense that all the computers are in their data centers - I’m not saying random support staff can read your data. I still think of all the resources in my accounts as my own, to do with as I please. Yet, I can’t edit these roles, nor remove them (sometimes), nor change their permissions. I can’t even create a regular role with a name beginning with “AWSServiceroleFor” in my accounts. Amazon is dictating what access it needs without any customer governance. Weird and maybe a little scary?

I mean, there is the concept of service roles and execution roles that AWS customers create and own, often with the help of a wizard or other template. Those roles feel like they fit the security model, so why not use those? I’m certain there’s a good reason.

Enumerate SLRs and their policies

There’s a pretty table in the IAM documentation that states which services use service-linked-roles. Is that table up to date and accurate? No. Does it give you an understanding of all the trust and resource policies? No.

Luckily, there is a (somewhat hidden) top sekret iamv2 service API. If you inspect the network traffic while using the AWS management console, you’ll see iamv2 being called regularly. That API has a getServiceLinkedRoleTemplate method that takes a single serviceName parameter. Service name is just the fully qualified AWS service name, ending in “amazonaws.com”, e.g. “ec2.amazonaws.com”.

The function returns some JSON that looks like this, which includes the full resource and trust policy to be used with the role:

{

"namedPermissionsPolicies": [

{

"policyName": "AccessAnalyzerServiceRolePolicy",

"policyId": "ANPAZKAPJZG4CAIXDDRI2",

"arn": "arn:aws:iam::aws:policy/aws-service-role/AccessAnalyzerServiceRolePolicy",

"path": "/aws-service-role/",

"defaultVersionId": "v17",

"createDate": "Dec 2, 2019, 5:13:10 PM",

"updateDate": "May 12, 2025, 3:52:06 PM",

"policyDocument": "..."

}

],

"awsServiceName": "access-analyzer.amazonaws.com",

"assumeRolePolicy": "...",

"roleNamePrefix": "AWSServiceRoleForAccessAnalyzer",

"isAllowMultipleRoles": false

}

So as long as we can come up with a comprehensive list of service names, then we can enumerate all the service-linked roles and their policies. Thankfully, the developer-friendly folks at AWS have recently published a programmatically accessible service reference, which we can use to make a solid list:

curl -s https://servicereference.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/v1/service-list.json \

| jq -r '.[].service + ".amazonaws.com"'

I’d love to tell you that this produces the full list, but sometimes we must say the hard thing, not the thing we want to say. Some hidden, region-based, non-prod, test, dev, whatever services aren’t in that list but it’s close enough. If you’re interested in a fuller list, you might want to play with Nick Frichette’s Undocumented AWS API Hunter. That still won’t be perfect, but that’s just AWS scale for you. Anyways, what we have is more than good enough.

Enjoy my personal list of service-linked role names here.

Check any account for service usage

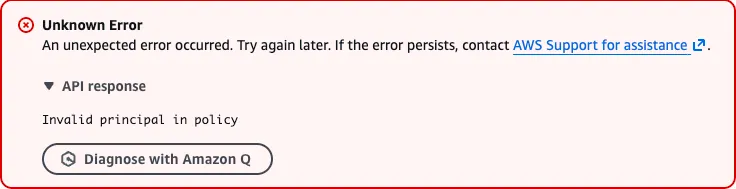

Back in 2016, a younger prettier version of me discovered a cool quirk in the AWS policy validation engine, that is present to this day. If you pass an invalid principal to a resource or trust policy, the policy validation engine will throw an error and tell you it doesn’t exist like so:

That means you can check for the existence of roles in any account, even those you don’t have access to, as long as you know their account ID and principal names that might reasonably exist. Since service-linked roles have predictable names, and they are often created when a service is first used, you can somewhat accurately check if any account is using a given (SLR enabled) service.

You can do this yourself with my original artisanal code, or do it industrial style with Quiet Riot, or do it like an alien on meth with Roles. If you’re interested in knowing more about what hackers know about your AWS account, check out this blog.

I’ll admit the relationship between a service-linked role existing and the service being actively used is somewhat tenuous - it could have been used once and never touched again for example. If you want to fool attackers and make it even more tenuous, you can create all the available service linked roles in your account programmatically using the aws iam create-service-linked-role API:

for svc in $(curl -s https://servicereference.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/v1/service-list.json | jq -r '.[].service + ".amazonaws.com"'); do

echo "Trying: $svc"

aws iam create-service-linked-role --aws-service-name "$svc" 2>&1

done

This will make it look like you are using all the services.

Enumerate resources without permission to list them

Imagine you have a policy like the one below, attached to your AWS user or role. It allows two IAM actions, DeleteServiceLinkedRole and GetServiceLinkedRoleDeletionStatus, but explicitly denies everything that is NOT either of those.

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "AllowSpecificIAMActions",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"iam:DeleteServiceLinkedRole",

"iam:GetServiceLinkedRoleDeletionStatus"

],

"Resource": "*"

},

{

"Sid": "ExplicitDenyAllOtherActions",

"Effect": "Deny",

"NotAction": [

"iam:DeleteServiceLinkedRole",

"iam:GetServiceLinkedRoleDeletionStatus"

],

"Resource": "*"

}

]

}

In theory you should not be able to list any resource in your AWS account.

For example, here’s me trying to list SageMaker domains with such a role:

% aws sagemaker list-domains --region ap-southeast-2

An error occurred (AccessDeniedException) when calling the ListDomains operation: User: arn:aws:sts::123456789012:assumed-role/dg-test-with-deny/dg-deny-test is not authorized to perform: sagemaker:ListDomains on resource: arn:aws:sagemaker:ap-southeast-2:123456789012:domain/* with an explicit deny in an identity-based policy

So far so good.

However, if I try to delete the service-linked role for SageMaker, this happens:

% TASK_ID=$(aws iam delete-service-linked-role \

--role-name AWSServiceRoleForAmazonSageMakerNotebooks \

--query 'DeletionTaskId' --output text)

% aws iam get-service-linked-role-deletion-status \

--deletion-task-id "$TASK_ID"

{

"Status": "FAILED",

"Reason": {

"Reason": "A service-linked role is required for managing Amazon SageMaker Studio domains. Try again after deleting all the domains in your account.",

"RoleUsageList": [

{

"Region": "ap-southeast-2",

"Resources": [

"arn:aws:sagemaker:ap-southeast-2:123456789012:domain/d-favr5gpmidva",

"arn:aws:sagemaker:ap-southeast-2:123456789012:domain/d-ldskx5dymwrb",

"arn:aws:sagemaker:ap-southeast-2:123456789012:domain/d-eviyaeotkfyc",

"arn:aws:sagemaker:ap-southeast-2:123456789012:domain/d-xspebcdlbc4d",

"arn:aws:sagemaker:ap-southeast-2:123456789012:domain/d-d14gz4fosoce"

]

}

]

}

}

Since the deletion task does the listing of SageMaker domains itself, presumably with access delegated to the service itself or other IAM dark magic, I get to see the output of that list operation without ever having performed it myself.

This works similarly for other services that still have resources at the time an attempt is made to delete their service-linked role.

Confused deputy protection is not required, probably (maybe definitely)

The confused deputy problem is confusing.

Think of it like this: You ask a powerful AWS service (like a Lambda) to do a small task for you, but because it can’t tell who’s really asking or why, someone else could trick it into using its higher permissions to do something you’re not allowed to.

Historically, AWS has been plagued by confused deputy issues. They’ve responded in many ways, including writing a lot of documentation on this topic. Try Googling "confused deputy" site:docs.aws.amazon.com to get a sense of the scope.

If you go to one of those service specific pages - I clicked the AWS Transfer Family one - you’ll often get some info on service roles or execution roles and how to formulate a secure trust policy. Here’s the AWS Transfer Family execution role trust policy:

{

"Version":"2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {

"Service": "transfer.amazonaws.com"

},

"Action": "sts:AssumeRole",

"Condition": {

"StringEquals": {

"aws:SourceAccount": "123456789012"

},

"ArnLike": {

"aws:SourceArn": "arn:aws:transfer:us-east-1:123456789012:user/*"

}

}

}

]

}

Notice it uses the aws:SourceAccount and aws:SourceArn conditions. These effectively say, when this role is assumed, it has to be as a result of an action by a principal in the account specified. The consequence of this is that another person in another account cant trick the transfer.amazonaws.com service into assuming that role.

Why am I telling you all of this? Well, since we now have all of the trust policies for all of the service-lined-roles we can inspect them and see how they do confused deputy protection. And… they don’t. Not a single one has a Condition statement.

Does that mean they can be used in confused deputy attacks? Probably not, but I’m not certain. AWS is more definitive (see their response at the end of this section).

It looks like at some point AWS made a change that uses iam:PassRole logic to deny service-linked roles. If you’re unfamiliar, iam:PassRole is both the action a principal requests and the permission they need to be allowed to perform it. In practice, it lets a user or service tell AWS, 'use this role,” so the target service can assume that role and act with its permissions. AWS seems to block this action for service-linked roles, which may be how they prevent confused deputy-style misuse, even though there are no explicit condition statements in the trust policies.

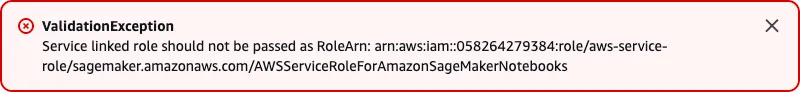

Here’s an example of me trying to use the CloudWatch service-linked-role as an execution role:

% aws events put-targets \

--rule dg-rule-test \

--region ap-southeast-2 \

--targets "Id"="test-queue-senal","Arn"="arn:aws:sqs:ap-southeast-2:123456789012:test-queue-senal","RoleArn"="arn:aws:iam::123456789012:role/aws-service-role/events.amazonaws.com/AWSServiceRoleForCloudWatchEvents"

An error occurred (ValidationException) when calling the PutTargets operation: Caller Account ID: 058264279384 is not authorized to perform: iam:PassRole on resource: arn:aws:iam::123456789012:role/aws-service-role/events.amazonaws.com/AWSServiceRoleForCloudWatchEvents because a service-linked role cannot be used with the iam:PassRole action. Use a service role instead.

Yet, I’ve found plenty of documentation online that suggests this should be possible, from Reddit threads to official AWS docs, like this one for AutoScaling:

I asked the AWS Vulnerability Disclosure Program (VDP) to clarify. Here’s the more definitive response I got:

All IAM roles are not subject to the confused deputy problem today because you cannot provide a role from another account (for both service roles and SLRs). You can only use the iam:PassRole permission to pass an IAM role to a service that shares the same AWS account

My 2c: This is probably accurate as a general statement assuming all instances of a role being passed to an AWS service are governed by iam:PassRole, which is for sure the intended design. However, intentions don’t always get along with reality, so I’m happy all those execution role templates have conditions protecting against confused deputy attacks, just in case.

Resource policies use some dubious practices

Before I start clowning on IAM policies like I’ve never assigned iam:* in a policy just to make it work, let’s acknowledge some things:

- Customers have to trust AWS to some degree. They use AWS, so there has to be some degree of trust. The cloud is just someone else’s computer - in this case, Amazon’s.

- AWS has invested a lot of money in security but complexity and target value dictates that bad hackin' stuff will eventually happen and probably already has.

- In the event of something going wrong, customers should still want to make it as annoying for attackers as possible, in order to limit the potential damage and increase the amount of time for bad actors/abuses to be detected and removed.

- Customers should therefore hold AWS to high standard on their policies, even if they trust them.

With that in mind, let the clowning begin.

Many of the service-linked role policies don’t scope actions to any subset of resources. They just throw out a * in the Resource field. Sometimes that’s required for certain functionality but many times it’s not, and when it’s not, it’s by definition not least privilege.

Here’s an example from the RDS service-linked role policy:

{

"Sid": "Ec2",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"ec2:AllocateAddress",

"ec2:AssociateAddress",

"ec2:AuthorizeSecurityGroupIngress",

"ec2:CreateCoipPoolPermission",

"ec2:CreateLocalGatewayRouteTablePermission",

"ec2:CreateNetworkInterface",

"ec2:CreateSecurityGroup",

"ec2:DeleteCoipPoolPermission",

"ec2:DeleteLocalGatewayRouteTablePermission",

"ec2:DeleteNetworkInterface",

"ec2:DeleteSecurityGroup",

...

"ec2:DisassociateAddress",

"ec2:ModifyNetworkInterfaceAttribute",

"ec2:ModifyVpcEndpoint",

"ec2:ReleaseAddress",

"ec2:RevokeSecurityGroupIngress",

"ec2:CreateVpcEndpoint",

"ec2:DescribeVpcEndpoints",

"ec2:DeleteVpcEndpoints",

"ec2:AssignPrivateIpAddresses",

"ec2:UnassignPrivateIpAddresses"

],

"Resource": "*"

}

I don’t know exactly how RDS works but I’m going to assume this makes sense because RDS runs on EC2, so some control of EC2 instances is necessary. But should RDS be able to allocate IP addresses to every instance, not just RDS instances? Or, should RDS be able to authorise ingress network access to non-RDS instances? Clearly there should be some restrictions. The question is how to implement them. And let me tell you, AWS services have given this a red hot go in all the ways.

Way 1: tag-based policies. Admirable but practically problematic. This paragraph used to read, “using tags bad”, but my boss didn’t think that sufficiently made the case.

Here is a condition from the Evidently policy:

"Condition": { "StringNotEquals": { "aws:ResourceTag/Owner": "Evidently" } }

Owner is a very common tag used by customers. In fact, it’s a recommended mandatory tag by Amazon’s own Guidance for Tagging on AWS. If that tag is already being used by a customer, the service using it will cause a collision and probably some unpredictable interactions with other policies and downstream systems. Imagine if that tag was used to assign costs to teams.

That’s a pretty unique case, so here are all the tags used in service-linked policy conditions:

AmazonConnectCampaignsEnabled

AmazonConnectEnabled

AmazonECSManaged

AmazonEVSManaged

AmazonFSx

AmazonFSx.FileSystemId

AmazonMWAAManaged

AmazonTimestreamInfluxDBManaged

AppIntegrationsManaged

aws:backup:source-resource

aws:cloudformation:stack-id

aws:elasticfilesystem:default-backup

AWSAppFabricManaged

AWSApplicationMigrationServiceManaged

AWSBatchServiceTag

AWSDeviceFarmManaged

AWSElasticDisasterRecoveryManaged

AWSLicenseManager

AWSNetworkFirewallManaged

AWSPCSManaged

bugbust

codeguru-reviewer

created-for-service

CreatedBy

DeployedBy

DevOps-Guru-Analysis

DevOps-GuruInsightSsmOpsItemRelated

eks:eks-cluster-name

emr-container:endpoint:managed-certificate

EnableAWSServiceCatalogAppRegistry

ExcludeFileContentFromNotifications

FMManaged

GuardDutyManaged

InstanceConnectEndpointId

LicenseManagerLinuxSubscriptions

ManagedByAmazonSageMakerResource

ManagedByCloudWatchNetworkMonitor

OpenSearchManaged

OSISManaged

Owner

Redshift

refactor-spaces:application-id

refactor-spaces:environment-id

refactor-spaces:route-id

ResourceCreatedBy

RTBFabricManaged

SecurityIncidentResponseManaged

SSMForSAPCreated

SSMForSAPManaged

VerifiedAccessManaged

VpcLatticeManaged

WorkSpacesWebManaged

Those probably aren’t common in customer environements but now customers have to recognize that those tags are reserved, required for services to function correctly, required for security to function correctly, and should not be overwritten by their customery concerns.

Oof. do you know anyone that tracks all of these? Do customers know these have a silent security impact? By extension do customers know that merely tagging a resource could give AWS access to it?

I played around a little to see if I could abuse these in some way. For example, I tried making a certain resource appear in a list in another service, by tagging it the right way. I couldn’t make anything work but to be fair I got bored pretty quickly. I’m willing to bet there are abuse cases here with cross-service access.

The crazy thing is that the list of tags above also has the solution to the problem. Notice the tags that start with the prefix aws:? Those tags are reserved for AWS use. Here’s what happened when I tried to start an EC2 instance with a random tag starting with that prefix:

An error occurred (InvalidParameterValue) when calling the RunInstances operation: Tag keys starting with 'aws:' are reserved for internal use

The namespace is already there and reserved. All of this could be solved simply by moving the tags to the reserved namespace. For example, if Evidently used aws:Owner instead of Owner, there would be no collision. Customers couldn’t change the security properties of those resources and cross-service access would be bound by the actions of the services themselves.

Finally, tag values on public resources can be enumerated too you knowzrite? If you don’t know there’s a tool called Conditional Love that can read tag values cross-account as long as the tag name is known.

Using tags bad. 🤷

Way 2: name-based policies. The idea is to use part of the resource name instead of a tag. It’s a similar concept and has similar problems.

If resource name prefixes were reserved, this would be a fine approach (the good fine, not the wife-says-it’s-fine fine). But they typically aren’t. The good news is resources cannot typically be renamed so it’s often not possible to mess with what AWS has access to, after the fact.

Here are all the S3 bucket naming conventions customers have to keep track of because they are in service-linked role policies:

arn:aws:s3:::*/AWSAppFabric/*

arn:aws:s3:::amazon-braket-*

arn:aws:s3:::amazon-connect-*

arn:aws:s3:::amazon-connect-*/*

arn:aws:s3:::aws-license-manager-service-*

arn:aws:s3:::aws-migrationhub-orchestrator-*

arn:aws:s3:::aws-waf-logs-security-lake-*

arn:aws:s3:::AWSIVS_*/ivs/*

arn:aws:s3:::codeguru-reviewer-*

arn:aws:s3:::codeguru-reviewer-*/*

arn:aws:s3:::dms-serverless-premigration-results-*

arn:aws:s3:::migrationhub-orchestrator-*

arn:aws:s3:::migrationhub-orchestrator-*/*

arn:aws:s3:::migrationhub-strategy-*

arn:aws:s3:::sms-app-*

Some services standardize this concept and reserve part of the namespace for AWS use only. For example, CloudWatch has a dedicated condition cloudwatch:namespace and uses it to prevent customers creating log groups starting with AWS/.

Here’s SES doing it well, with none of the previously mentioned downsides, proving it can be done well:

{

"Sid": "AllowPutMetricDataToSESCloudWatchNamespaces",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": "cloudwatch:PutMetricData",

"Resource": "*",

"Condition": {

"StringLike": {

"cloudwatch:namespace": [

"AWS/SES",

"AWS/SES/MailManager",

"AWS/SES/Addons"

]

}

}

}

You probably get it by now but I will mention one more incarnation of this problem, Secrets Manager secrets. There are a bunch of policies that allow AWS to retrieve secrets from your SecretsManager which gives me the ick.

Any secret starting with “Panorama” can be read and deleted by AWS. Luckily Panorama is going away in May 2026.

{

"Sid": "SecretsManagerPermissions",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"secretsmanager:GetSecretValue",

"secretsmanager:DescribeSecret",

"secretsmanager:CreateSecret",

"secretsmanager:ListSecretVersionIds",

"secretsmanager:DeleteSecret"

],

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:secretsmanager:*:*:secret:panorama*",

"arn:aws:secretsmanager:*:*:secret:Panorama*"

]

}

Here’s Kafka with the ability to change who has access to secrets starting with “AmazonMSK_”:

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"secretsmanager:PutResourcePolicy",

],

"Resource": "*",

"Condition": {

"ArnLike": {

"secretsmanager:SecretId": "arn:*:secretsmanager:*:*:secret:AmazonMSK_*"

}

}

}

Linux subscriptions in License Manager can get any * secret value (oof) but have the interesting condition of requiring both a tag (which we know is not great) and this condition which is great model that AWS could more:

"Condition": { "StringEquals": {"aws:ResourceAccount": "${aws:PrincipalAccount}" }}

The condition says the account ID of the principal, in this case a service-linked role, must be the same as the account ID of the resource being accessed. This prevents cross-account style issues which is important for resources that are exposable cross account.

If another account (Account B) has given your account (Account A) access to a resource that’s accessible cross-account, all the AWS-owned service-linked roles in your account (Account A) also have access to the resource in Account B, which is not intended. There’s a transitive trust that Account B doesn’t know about and can only infer. Luckily, none of the policies I reviewed explicitly allowed iam:AssumeRole actions.

There’s another insidious bad practice in theses policies that’s worth mentioning, and that’s privilege escalation. Some permissions or combinations of permissions actually allow privileges to be increased beyond the scope of a give policy. So although the policy itself might look innocuous, it could be used to do more than what is immediately obvious.

For example, this section from Application Migration Service service-linked role policy actually gives it the power to do anything an an EC2 instance execution role can do. That’s because ModifyInstanceAttribute can be used to change user data startup scripts and StopInstances plus StartInstances in combination can be used to induce the script execution. Here’s a script to do this from 2016 that works do this day.

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"ec2:StartInstances",

"ec2:StopInstances",

"ec2:TerminateInstances",

"ec2:ModifyInstanceAttribute",

"ec2:GetConsoleOutput",

"ec2:GetConsoleScreenshot"

],

"Resource": "arn:aws:ec2:*:*:instance/*",

"Condition": {

"Null": {

"aws:ResourceTag/AWSApplicationMigrationServiceManaged": "false"

}

}

}

Similarly when a role has ssm:SendCommand permissions with document/AWS-RunPowerShellScript or AWS-RunShellScript, that’s effectively giving it the power to run code in the context of the instance execution role and whatever privileges it has.

Here’s an example from the Directory Service service-linked-role:

{

"Sid": "SSMSendCommandPermission",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"ssm:SendCommand"

],

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:ssm:*:*:document/AWS-RunPowerShellScript",

"arn:aws:ec2:*:*:instance/*"

]

}

There are other privilege escalation vectors that Plerion can identify but you get the point. Here is a list of 40+ that is maintained by Hacking The Cloud.

What service-linked-roles do you have?

If you are worried or interested in your exposure, it’s super easy to find all of the service-linked roles in your account:

aws iam list-roles \

--query 'Roles[?starts_with(Path, `/aws-service-role/`)].[RoleName, Path]' \

--output table

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| ListRoles |

+--------------------------------------------------------+------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| AWSServiceRoleForAccessAnalyzer | /aws-service-role/access-analyzer.amazonaws.com/ |

| AWSServiceRoleForAmazonEKS | /aws-service-role/eks.amazonaws.com/ |

| AWSServiceRoleForAmazonEKSForFargate | /aws-service-role/eks-fargate.amazonaws.com/ |

| AWSServiceRoleForAmazonEKSNodegroup | /aws-service-role/eks-nodegroup.amazonaws.com/ |

| AWSServiceRoleForAmazonEMRServerless | /aws-service-role/ops.emr-serverless.amazonaws.com/ |

| AWSServiceRoleForAmazonGuardDuty | /aws-service-role/guardduty.amazonaws.com/ |

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Conclusion and call to action

Buy yourself some Milo if you don’t currently own any. Everyone should have a personal tin of Milo.

For AWS customers:

- Consider creating all SLRs in your accounts to prevent service usage enumeration.

- Make sure you don’t collide with reserved or special-purposes tags and resource naming conventions.

For AWS:

- Update the APIs which list resources by proxy, without requiring list privileges.

- Add the confused deputy protections to SLR trust policies, even if they aren’t strictly necessary.

- Tighten SLR policies closer to least privilege, and avoid using unreserved namespaces.

- Add same account access restrictions to SLR policies.

- Look for and where possible remove privilege escalation permissions combinations from SLR policies.

For everyone else:

- Don’t do drugs.

Did you know that IAM role names have to be unique regardless of their path? Congratulations you made it to the end, and knowledge is your reward.